Monday, June 19, 2017

Once More Arthur's [Last Four] Battles (a little tribute there to Kenneth H. Jackson's famous Arthurian essay)

Aerial View of Eynsham Park Camp

Readers of my previous posts will recall that I discussed Arthur's last four battles in relationship to the prior engagements, which were all reflections of entries for Cerdic in the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle. I was bothered by the fact that after the Wihtgarasburh battle (= the Castle Guinion of Arthur), the other battles seemed to be tagged on in order to round out the number to a mythological, Zodiacal twelve. These extra battles seemed, superficially, at least, to have nothing to do with any of the other battles listed for the Gewissei in the ASC.

I now have reason to think I may have been mistaken. I had mentioned before that Arthur's City of the Legion battle may well be an attempt at the ASC's Limbury of 571, whose early forms are Lygean-, Liggean- and the like. I discounted the possibility solely because the next battle-site, that of the shore of the Tribruit, was certainly for the Trajectus on the Somerset Avon or over the Severn.

There is a problem, though, with identifying Tribruit with the Avon or Severn Trajectus, viz. there were doubtless many trajecti in Britain! And, indeed, Rivet and Smith (The Place-Names of Roman Britain, p. 178) discuss the term, saying that in some cases "it seems to indicate a ferry or ford..." Furthermore, although the Welsh rendered 'litore' of the Tribruit description in Nennius as 'traeth', demanding a river estuary emptying into the sea, litore (from Latin litus) could also mean simply 'river-bank'. Thus traeth could well be an improper rendering of the word.

If I were to look at Tribruit in this light, and provisionally accepted the City of the Legion as Limbury, and Badon as Bath (which the spelling demands, and which appears in a group of cities captured by Cerdic's father Ceawlin/Maquicoline/Cunedda), then the location of the Tribruit/Trajectus in question may well be determined by the locations of Mounts Agned and Breguoin. These last two battle-sites fall between those of the City of the Legion and Bath, and after that of the Tribruit.

I decided to take a fresh look at Agned, which has continud to vex Arthurian scholars. I noticed that in the ASC 571 entry there was an Egonesham, modern Eynsham. Early forms of this place-name include Egenes-, Egnes-, Eghenes-, Einegs-. According to both Ekwall and Mills, this comes from an Old English personal name *Aegen. Welsh commonly adds -edd to make regular nominative i:-stem plurals of nouns (information courtesy Dr. Simon Rodway, who cites several examples). Personal names could also be made into place-names by adding the -ydd suffix. The genitive of Agnes in Latin is Agnetus, which could have become Agned in Welsh - as long as <d> stands for /d/, which would be exceptional in Old Welsh (normally it stands for what is, in Modern Welsh, spelled as <dd>). I'd long ago shown that it was possible for Welsh to substitute initial /A-/ for /E-/. What this all tells me is that Agned could conceivably be an attempt at the hill-fort named for Aegen.

http://www.pastscape.org.uk/hob.aspx?hob_id=334760&sort=2&type=&typeselect=c&rational=a&class1=None&period=None&county=None&district=None&parish=None&place=eynsham%20park%20camp&recordsperpage=10&source=text&rtype=&rnumber=

But what of Mount Breguoin? Well, I had remembered that prior to his later piece on Breguoin ('Arthur's Battle of Breguoin', Antiquity 23 (1949) 48—9), Jackson had argued (in 'Once Again Arthur's Battles') that the place-name might come from a tribal name based on the Welsh word breuan, 'quern.' The idea dropped out of favor when Jackson ended up preferring Brewyn/Bremenium in Northumberland for Breguoin.

So how does seeing breuan in Breguoin help us?

In the 571 ASC entry we find Aylesbury as another town that fell to the Gewessei. This is Aegelesburg in Old English. I would point to Quarrendon, a civil parish and a deserted medieval village on the outskirts of Aylesbury. The name means "hill where mill-tones [querns] were got". Thus if we allow for Breguoin as deriving from the Welsh word for quern, we can identify this hill with Quarrendon at Aylesbury.

http://www.pastscape.org.uk/hob.aspx?hob_id=344409

http://www.pastscape.org.uk/hob.aspx?hob_id=342696

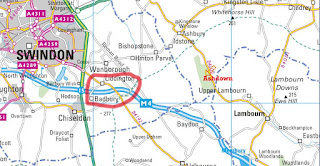

All of which brings us back, rather circuitously, to Tribruit. Taking this for a ford, the obvious candidate given Limbury, Aylesbury and Eynsham, is Bedcanforda of 571. This is also found as Biedcanforda and is believed by most to be Bedford (Bedanford, Bydanford, Bedefort, 'Bieda's Ford'). I would not hesitate, therefore, to propose that the Tribruit river-bank is the trajectus at Bedford.

If we accept all this, then we cannot very easily reject Badon as Bath. In truth, with Bath listed in the ASC entry for 577, and made into a town captured by Ceawlin, we simply are no longer justified in trying to make a case for the linguistically impossible Badbury at Liddington.

Sunday, June 18, 2017

Friday, June 16, 2017

Thursday, June 15, 2017

Wednesday, June 14, 2017

Monday, June 12, 2017

Concerning the Second Battle of Badon

Ashdown's Proximity to Liddington Castle/Badbury

In the past I've discussed the very strong probability that the Second Battle of Badon in the Welsh Annals represents not a later engagement at Bath in Somerset, but at the Badbury of Liddington in Somerset:

http://mistshadows.blogspot.com/2017/01/arthurs-badon-at-last-evidence-for.html

I now believe this is the best argument in support of the first Badon being not Bath, but Liddington Castle. Again, I must emphasize that Badon, when treated of solely linguistically, cannot be Badbury. What I've been proposing all along is that Badon has been confused for and thus substituted for Baddan(-byrig) in the Welsh sources.

According to Pastscape (http://www.pastscape.org/hob.aspx?hob_id=225540), there is a hill-fort at Ashdown. As the Mercian king was raiding into Wessex, it is entirely conceivable that his path took him through Liddington/Badbury or at at least along the Roman road that ran immediately to the east of the area.

Alfred's Castle hill-fort at Ashdown

For me, this identification of 'Badon' as the Liddington Badbury, combined with the presence of Cerdic's/Ceredig's/Arthur's father Ceawlin's at nearby Barbury (the BEAR'S FORT), and with the perfect correspondence of the Welsh place-names Breguoin and Liddington (both being based on roots meaning a roaring stream), comes as near as we can to clinching the case for Arthur's Badon = the Liddington Badbury.

Monday, June 5, 2017

Badbury Rather than Bath: My Final Decision on the Matter

Map Showing Barbury and Liddington Castles

Connected by the Ancient Ridgeway

In past blog articles, I've gone back and forth on whether to favor Bath in Somerset or the Badbury at Liddington Castle in Wiltshire as Arthur's Badon. I've made it clear that while the spelling Badon MUST relate to Bath, it could well be that this place became accidentally substituted for the Liddington Badbury.

I've come to realize that I really can't offer anything other than a logical argument in favor, ultimately, of the Liddington Badbury.

While Agned as deriving from Agnetis, the genitive of Agnes the virgin saint, looks good linguistically, as we cannot demonstrate that St. Agnes was EVER present at Bath as a Christian substitute for Sulis Minerva, I don't feel I can support this idea any longer. It is clever, but not convincing.

On the other hand, there is no doubt whatsoever that Breguoin does, in fact, represent Brewyn/Bremenium, a Roman fort found in the Cheviots of Northumberland. However, as I've demonstrated before in some detail, the meaning of the root of Breguoin has exactly the same meaning as the root of the place-name Liddington, an alternate name for the Wiltshire Badbury hill-fort. We have also seen that Cerdic's/Ceredig's/Arthur's father Ceawlin/Maquicoline/Cunedda fought at Barbury Castle or the 'Fort of the Bear', only a very short distance from the Liddington Badbury along the ancient Ridgeway. It is very possible that the English called Barbury the Bear's Fort because Arthur was there in some capacity (the Welsh arth meaning 'bear'). Granted, we are also told in the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle that Ceawlin took Bath.

Agned is easily dispensed with. I discussed how in my book THE ARTHUR OF HISTORY, and cited top Celticists in support of the idea I presented there. What I did was to adopt Dr. Andrew Breeze's quite sensible proposal that Agned was a misspelling of agued (the n > u copying error is a common one), a known Welsh word which simply means "distress, dire straits" or the like. In other words, the host or hosts at Liddington Castle/Badbury were in 'dire straits, difficulty, anxiety' (suggested meanings provided by Dr. Graham Isaac). Agned is thus not a real place-name at all, but instead a poetic descriptor of what happened at the battle.

For now, I will remain content with this analysis of the Agned and Breguoin place-names - until and if I encounter evidence or a counter-argument which convinces me otherwise.

Friday, June 2, 2017

A Radical Reappraisal of the Last Four Battles of Cerdic/Ceredig/Arthur

In past articles, I've struggled with proper identifications for the following Arthurian battles:

a) City of the Legion

b) the Tribruit Shore

c) Mount Agned or Mount Breguoin/Bregion/Bregomion

d) Mount Badon

In this new piece, I wish to explore these sites anew. This time, instead of concentrating solely on linguistic matches, I want to compare the first grouping of Arthurian battles from a strategic standpoint with the latter ones. When considering this we have to remember that the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle for some strange reason REVERSES the genealogical order of the Gewessei princes. Hence the chronology of the ASC battles is seriously flawed.

The Glein, Bassas, Dubglas, Celyddon and Guinnion battles all can be firmly located between the Hampshire Avon, Southhampton Water and the Isle of Wight. These battles indicate raiding from the sea. They also suggest a distinctive method of penetration into hostile territory: following river valleys from their terminus to their source. Cerdic eventually reached Charford on the Avon, or perhaps a bit further (depending where we situate the unlocated Cerdicesleag). After the "conquest" of Wight, Cynric/Cunorix son of Maquicoline/Ceawlin (= Cunedda) defeats the British at Old Sarum hard by Salisbury. This battle is on the same River Avon as Charford, only more to the north. Again, the river is being followed into the heartland of the enemy.

Something odd then happens with the next battle, fought by Ceawlin. The site is Barbury Castle in Wiltshire, far to the north of the Hampshire Avon. However, Barbury or Beranbyrig is the "Bear's Fort" (or the fort of someone named Bear), and I've believed for some time now that this was an English designation for Arthur (as arth in Welsh means 'bear'). Barbury, in turn, is very close to the Liddington Castle Badbury.

Ceawlin's next battle (568) marks another major departure from prior arenas of conflict. He is said to have driven Aethelberht into Kent and to have slain two princes at Wibbandun. The location of Wibbandun is unknown. However, given the villages said to have been captured in 571 (Limbury, Aylesbury, Benson and Eynsham), we can probably place it at or near Whipsnade (detached plot of a man called Wibba; Mills, A Dictionary of English Place-Names), Bedfordshire. These places were supposedly taken by Ceawlin's BROTHER Cutha. Cutha is a hypocoristic form of something like the Cuthwulf or Cuthwine mentioned as fighting alongside Ceawlin. As I've pointed out before, the name derives from the goddess name Cuda, who is remembered in the regional designation The Cotswolds. In 577 it is Ceawlin and Cuthwine who fight at Dyrham and who slay three kings (one of them - Coinmail - bears the same name as that of Apollo Cunomaglos, whose shrine was near the Dyrham battle site). The cities of Gloucester, Cirencester and Bath are taken as a consequence.

So what now to do with the last 4 battles of Arthur? If we assume for the sake of argument they are not simply fanciful additions to the list, meant to pad it out to the desired Herculean 12...

It has occurred to me that the City of the Legion could be Limbury from the ASC, as the first part of this place-name is variously spelled Lygean- or Liggean-. It would not take much for a monkish scribe to have mistakenly related Lygean-/Liggean- to legionis, the genitive singular of legio. Badon would thus be Ceawlin's Bath. But Caerleon cannot be discounted for the City of the Legion, especially as the Pierced-Through Shore that is Traeth Tribruit can only be the Trajectus that crossed from Caerwent near Caerleon to a spot on Bath's River Avon.

And this leaves the very troublesome Agned and Breguoin/Bregion/Bregomion to untangle. At one time I pitched W. Agned as directly derived from the Latin genitive Agnetis, for Agnes the virgin saint. This is perfect linguistically. My idea was that this Christian virgin's name had replaced that of Sulis Minerva (Minerva being the ultimate virgin Roman goddess) which we find preserved at Little Solsbury Hill overlooking Bath. Mount Agned and Mount Badon would then be one and the same place. Yet Agned could also be an easily accountable error for Welsh agued, a mere adjective meaning that the host or hosts at Mount Badon were in straits or distress. In this case it would not be a proper name at all.

Breguoin, while perfect for Brewyn/Bremenium in Northumberland, could also be a Welsh substitute for the Liddington of Liddington Castle, Badbury. This is because the meanings of the roots of the Welsh and English words mean the same thing. 'Badon' would then be an incorrect substitution of Bath for a Baddan(byrig). Bregion is simply a plural form meaning 'hills', and it can be nicely associated with Brean Down promontory hill-fort in Somerset. Or it can be a generic terms for any grouping or range of hills - a fact that is spectacularly unhelpful. Bregomion looks to be merely a strange combination of Breguoin and Bregion! In other words, a corruption.

How to resolve these problems?

I'm now thinking all my attempts to make something of Breguoin/Bregion/Bregomion have been for naught. We must remember that the Welsh word for hill, bre, has the same Indo-European root origin as the English word beorg. And that the Old English word for fort - burh - is also from the same root.

From the GPC on bre:

If Arthur went from Caerleon to Caerwent and thence via the Trajectus over the Severn to the River Avon, and his very last victorious battle is Badon (whose spelling beyond a doubt does indicate Bath), then the Agned-burg or Agned-burgs in question must be between the Trajectus landing place (possibly Bitton) and Bath itself. Brean Down can no longer be considered an acceptable candidate.

I am here going to propose that the Hills of Agned are Little Solsbury Hill camp and the Southampton Down camp, both of which stand over Bath on opposite sides of the River Avon. While we have no extant evidence that St. Agnes was ever known here, I feel it is not unreasonable to assume that at least in this case she was chosen as an approved Christian substitute for Sulis Minerva. The hill-forts above Bath were sacred to her, of course, and control of both had to be wrested from their owners by Ceawlin/Cunedda and his son, Cerdic/Ceredig/Arthur.

a) City of the Legion

b) the Tribruit Shore

c) Mount Agned or Mount Breguoin/Bregion/Bregomion

d) Mount Badon

In this new piece, I wish to explore these sites anew. This time, instead of concentrating solely on linguistic matches, I want to compare the first grouping of Arthurian battles from a strategic standpoint with the latter ones. When considering this we have to remember that the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle for some strange reason REVERSES the genealogical order of the Gewessei princes. Hence the chronology of the ASC battles is seriously flawed.

The Glein, Bassas, Dubglas, Celyddon and Guinnion battles all can be firmly located between the Hampshire Avon, Southhampton Water and the Isle of Wight. These battles indicate raiding from the sea. They also suggest a distinctive method of penetration into hostile territory: following river valleys from their terminus to their source. Cerdic eventually reached Charford on the Avon, or perhaps a bit further (depending where we situate the unlocated Cerdicesleag). After the "conquest" of Wight, Cynric/Cunorix son of Maquicoline/Ceawlin (= Cunedda) defeats the British at Old Sarum hard by Salisbury. This battle is on the same River Avon as Charford, only more to the north. Again, the river is being followed into the heartland of the enemy.

Something odd then happens with the next battle, fought by Ceawlin. The site is Barbury Castle in Wiltshire, far to the north of the Hampshire Avon. However, Barbury or Beranbyrig is the "Bear's Fort" (or the fort of someone named Bear), and I've believed for some time now that this was an English designation for Arthur (as arth in Welsh means 'bear'). Barbury, in turn, is very close to the Liddington Castle Badbury.

Ceawlin's next battle (568) marks another major departure from prior arenas of conflict. He is said to have driven Aethelberht into Kent and to have slain two princes at Wibbandun. The location of Wibbandun is unknown. However, given the villages said to have been captured in 571 (Limbury, Aylesbury, Benson and Eynsham), we can probably place it at or near Whipsnade (detached plot of a man called Wibba; Mills, A Dictionary of English Place-Names), Bedfordshire. These places were supposedly taken by Ceawlin's BROTHER Cutha. Cutha is a hypocoristic form of something like the Cuthwulf or Cuthwine mentioned as fighting alongside Ceawlin. As I've pointed out before, the name derives from the goddess name Cuda, who is remembered in the regional designation The Cotswolds. In 577 it is Ceawlin and Cuthwine who fight at Dyrham and who slay three kings (one of them - Coinmail - bears the same name as that of Apollo Cunomaglos, whose shrine was near the Dyrham battle site). The cities of Gloucester, Cirencester and Bath are taken as a consequence.

So what now to do with the last 4 battles of Arthur? If we assume for the sake of argument they are not simply fanciful additions to the list, meant to pad it out to the desired Herculean 12...

It has occurred to me that the City of the Legion could be Limbury from the ASC, as the first part of this place-name is variously spelled Lygean- or Liggean-. It would not take much for a monkish scribe to have mistakenly related Lygean-/Liggean- to legionis, the genitive singular of legio. Badon would thus be Ceawlin's Bath. But Caerleon cannot be discounted for the City of the Legion, especially as the Pierced-Through Shore that is Traeth Tribruit can only be the Trajectus that crossed from Caerwent near Caerleon to a spot on Bath's River Avon.

And this leaves the very troublesome Agned and Breguoin/Bregion/Bregomion to untangle. At one time I pitched W. Agned as directly derived from the Latin genitive Agnetis, for Agnes the virgin saint. This is perfect linguistically. My idea was that this Christian virgin's name had replaced that of Sulis Minerva (Minerva being the ultimate virgin Roman goddess) which we find preserved at Little Solsbury Hill overlooking Bath. Mount Agned and Mount Badon would then be one and the same place. Yet Agned could also be an easily accountable error for Welsh agued, a mere adjective meaning that the host or hosts at Mount Badon were in straits or distress. In this case it would not be a proper name at all.

Breguoin, while perfect for Brewyn/Bremenium in Northumberland, could also be a Welsh substitute for the Liddington of Liddington Castle, Badbury. This is because the meanings of the roots of the Welsh and English words mean the same thing. 'Badon' would then be an incorrect substitution of Bath for a Baddan(byrig). Bregion is simply a plural form meaning 'hills', and it can be nicely associated with Brean Down promontory hill-fort in Somerset. Or it can be a generic terms for any grouping or range of hills - a fact that is spectacularly unhelpful. Bregomion looks to be merely a strange combination of Breguoin and Bregion! In other words, a corruption.

How to resolve these problems?

I'm now thinking all my attempts to make something of Breguoin/Bregion/Bregomion have been for naught. We must remember that the Welsh word for hill, bre, has the same Indo-European root origin as the English word beorg. And that the Old English word for fort - burh - is also from the same root.

From the GPC on bre:

bre1

[Crn. Bray, Brea (e. lleoedd), Llyd. C. Bre (Levenez) (e. lle), Llyd. Diw. bre: < Clt. *brigā, o’r gwr. IE. *bhr̥ĝh- ‘uchel, dyrchafedig’, cf. Gal. Nemeto-briga, Nerto-briga, Alm. Berg; â’r ll. breon, cf. 9g. Hist Brit c. 56 Bregion (e. lle); a cf. H. Wydd. brí (gen. breg): < Clt. *brixs; tebyg mai cfl. traws bre1 a welir yn fry ac obry; cf. hefyd braint1, brenin]

eg.b. ll. breon, breoedd, a hefyd fel a. ac adf.

Bryn, bryncyn, mynydd, bryndir, ucheldir, copa, hefyd yn ffig.:

hill, hillock, mountain, hill-country, upland, peak, also fig.

We see here the OW bregion and MW breon for "hills".

And here is burh and beorg from the Bosworth/Toller AS dictionary:

BURH, burg; gen. burge; dat. byrig, byrg; acc. burh, burg; pl. nom. acc. burga; gen. burga; dat. burgum; f. [beorh, beorg = burh, burg the impert. of beorgan to defend]. I. the original signification was arx, castellum, mons, a castle for defence. It might consist of a castle alone; but as people lived together for defence and support, hence a fortified place, fortress, castle, palace, walled town, dwelling surrounded by a wall or rampart of earth; arx, castellum, mons, palatium, urbs munita, domus circumvallata :-- Se Abbot Kenulf macode fyrst ða wealle abútan ðone mynstre, [and] geaf hit ðá to nama Burh [Burch MS.], ðe æ-acute;r hét Medeshámstede the Abbot Kenulf first made the wall about the minster, and gave it then the name Burh = Burg [Petres burh Peter's burg = Peterborough] , which before was called Meadow-home-stead, Chr. 963; Erl. 123, 27-34; Th. 221, 34-39. ILLEGIBLE The style of the Anglo-Saxon indicates a late date, perhaps about 1100 or 1200. Burg arx, Cot. 10. Stíþlíc stán-torr and seó steépe burh on Sennar stód the rugged stone-tower and the high fortress stood on Shinar, Cd. 82; Th. 102, 15; Gen. 1700. Óþ ðæt hie on Sodoman weall-steápe burg wlitan meahton till they on Sodom's lofty-walled fortress might look, 109; Th. 145, 7; Gen. 2402. Ðæ-acute;r se hálga heáh, steáp reced, burh timbrede there the holy man built a high, steep dwelling, a walled town, 137; Th. 172, 6; Gen. 2840. Burge weall the wall of a city; murus, Ps. Th. 17, 28. Ðæt hie geseón mihten ðære wlitegan byrig weallas that they might see the walls of the beautiful city, Judth. 11; Thw. 23, 24; Jud. 137: Ps. Th. 44, 13: 47, 11. On leófre byrig and háligre in montem sanctificationis suæ, 77, 54: 77, 67. Ðá férdon híg þurh ða burhga egressi circuibant per castella. Lk. Bos. 9, 6. Eádweard cyng fór mid fierde to Bedan forda, and beget ða burg king Edward went with an army to Bedford, and gained the walled town, Chr. 919; Th. 192, 24, col. l. Ge binnan burgum, ge búton burgum both within walled towns, and without walled towns, L. Edg. S. 3; Th. i. 274, 7. Ðone æðeling on ðære byrig métton, ðér se cyning ofslægen læg they found the ætheling in the inclosure of the dwelling, where the king lay slain, Chr. 755; Th. 84, 19, col. 1: L. Edm. S. 2; Th. i. 248, 16: L. Eth. iii. 6; Th. i. 296, 5. II. a fortress or castle being necessary for the protection of those dwelling together in cities or towns, -- a city, town, burgh, borough; urbs, civitas, oppidum :-- Róma burh the city Rome, Bd. 1. 11; S. 480, 10, 12. Ða ðe in burh móton gongan, in Godes ríce they may go into the city, [may go] into God's kingdom, Cd. 227; Th. 303, 16; Sae. 613. Ðonne hý hweorfaþ in ða hálgan burg when they pass into the holy city, Exon. 44b; Th. 150, 26; Gú. 784. Ðæt he gesáwe ða burh ut videret civitatem, Gen. ll, 5. Ða burh ne bærndon they burnt not the city, Ors. 2, 8; Bos. 52, 8. Burge weard the guardian of the city, Cd. 180; Th. 226, 19; Dan. 173: Ps. Th. 9, 13. Ðonne hí eów éhtaþ on ðysse byrig cum perseguentur vos in civitate ista, Mt. Bos. 10, 23: Exon. 15b; Th. 34, 14; Cri. 542. Binnan ðære byrig within the city, Ors. 2, 8; Bos. 52, 4. Beóþ byrig mid Iudém getimbrade ædificabuntur civitates Judæ, Ps. Th. 68, 36. Byrig fægriaþ towns appear fair, Exon. 82a; Th. 308, 32;

Seef. 48. Ðá ongan he hyspan ða burga tunc cæpit exprobrare civitatibus, Mt. Bos. ll, 20. On burgum in the towns, Beo. Th. 105; B. 53. [Piers P. Chauc. burghe: R. Brun. burgh: R. Glouc. bor&yogh;: Laym. burh: Orm. burrh: Plat. borch, f: O. Sax. burg, f. urbs, civitas: Frs. borge, m. f: O. Frs. burch, burich, f: Dut. burgt, f: Kil. borg, borght: Ger. burg, f. arx, castellum: M. H. Ger. burc, f: O. H. Ger. buruc, burg, f. urbs, civitas: Goth. baurgs, f: Dan. borg, m. f: Swed. borg, m: O. Nrs. borg, f.] DER. ealdor-burh [-burg], fóre-, freó-, freoðo-, gold-, heáfod-, heáh- [heá-], hleó-, hord-, in-, leód-, mæ-acute;g-, medo-, meodu-, rand-, rond-, sceld-, scild-, scyld-, stán-, under-, weder-, wín-, wyn-.

beorg, beorh, biorg, biorh; gen. beorges; dat. beorge; pl. nom. acc. beorgas; gen. beorga; dat. beorgum; m. I. a hill, mountain; collis, mons :-- On Sýne beorg on Sion's hill, Exon. 20 b; Th. 54, 29; Cri. 876. Óþ ða beorgas ðe man hæ-acute;t Alpis to the mountains which they call the Alps, Ors. 1, 1; Bos. 18, 44; 16, 17. Æ-acute;lc múnt and beorh byþ genyðerod omnis mons et collis humiliabitur, Lk. Bos. 3, 5. Æt ðæm, beorge ðe man Athlans nemneþ at the mountain which they call Atlas, Ors. 1, 1; Bos. 16, 6. II. a heap, BURROW or barrow, a heap of stones, place of burial; tumulus :-- Worhton mid stánum ánne steápne beorh him ofer congregaverunt super eum acervum magnum lapidum, Jos. 7, 26. Bæd ðæt ge geworhton in bæ-acute;lstede beorh ðone heán he commanded [bade] that you should work the lofty barrow on the place of the funeral pile, Beo. Th. 6186; B. 3097 : 5606; B. 2807 : Exon. 50 a; Th. 173, 26; Gú. 1166 : 119 b; Th. 459, 31; Hö. 8. [Laym. berh&yogh;e : Piers bergh; still used in the dialect of Yorkshire : Plat. barg : O. Sax. berg : O. Frs. berch, birg : Ger. berg : M. H. Ger. berc : O. H. Ger. perac : Goth. bairga-hei a mountainous district : Dan. bjærg, n : Swed. berg, n : O. Nrs. berg, n : derived from beorgan.] DER. ge-beorg, -beorh, heáh-, mund-, sæ-acute;-, sand-, stán-.

Finally, the evidence for the common IE root for these hill words may be found here:

https://lrc.la.utexas.edu/lex/master/0239

https://lrc.la.utexas.edu/lex/master/0239

What I'm hinting at is that Agned and Breguoin/Bregion/Bregomion may originally have been a single COMPOUND PLACE-NAME. The first element was Agned-, while the second was -bury. In other words, the Welsh chose to use their own breg for burg, and this word was further altered through careless Latinization. Or, if we wish to preserve the plural, we are talking here about the "burgs of Agned".

If Arthur went from Caerleon to Caerwent and thence via the Trajectus over the Severn to the River Avon, and his very last victorious battle is Badon (whose spelling beyond a doubt does indicate Bath), then the Agned-burg or Agned-burgs in question must be between the Trajectus landing place (possibly Bitton) and Bath itself. Brean Down can no longer be considered an acceptable candidate.

I am here going to propose that the Hills of Agned are Little Solsbury Hill camp and the Southampton Down camp, both of which stand over Bath on opposite sides of the River Avon. While we have no extant evidence that St. Agnes was ever known here, I feel it is not unreasonable to assume that at least in this case she was chosen as an approved Christian substitute for Sulis Minerva. The hill-forts above Bath were sacred to her, of course, and control of both had to be wrested from their owners by Ceawlin/Cunedda and his son, Cerdic/Ceredig/Arthur.

Little Solsbury Hill and Southampton Down

NOTE: Here is my earlier piece on Sulis Minerva and St. Agnes:

http://mistshadows.blogspot.com/2017/01/mount-agned-st-agnes-and-minervasulis.html

http://mistshadows.blogspot.com/2017/01/mount-agned-st-agnes-and-minervasulis.html

Friday, May 26, 2017

The Irish Cunedda (A Selection From My Book, THE ARTHUR OF HISTORY)

Posting this because several people have requested to read my argument for Cunedda's origin in Ireland rather than in Manau Gododdin. Several of my recent articles on Ceredig son of Cunedda as Arthur depend in large part on being able to successfully demonstrate that Ceredig = Cerdic of Wessex. And to do that, I have to first provide evidence for the true nature of the Gewissae. So here is the relevant selection from my earlier book, setting out my reasoning for identifying Cunedda as an Irish chieftain and not a Northern British one...

Cunedda

The great Cunedda, called Cunedag (supposedly from *Cunodagos, ‘Good Hound’) in the Historia Brittonum, is said to have come down (or been brought down) from Manau Gododdin, a region around the head of the Firth of Forth, to Gwynedd. This chieftain and his sons then, according to the account found in the HB, proceeded to repulse Irish invaders. Unfortunately, this tradition is largely mistaken. To prove that this is so, we need to begin by looking at the famous Wroxeter Stone, found at the Viroconium Roman fort in what had been the ancient kingdom of the Cornovii, but which was the kingdom of Powys in the Dark Ages.

The Wroxeter Stone is a memorial to a chieftain named Cunorix son of Maquicoline. This stone has been dated c. 460-75 CE. Maquicoline is a composite name meaning Son [Maqui-] of Coline. The resemblance here of Cunorix and Coline to the ASC's Cynric and his son Ceawlin is obvious. Some scholars would doubtless say this is coincidence, and that the discrepancy in dates for Cynric and Ceawlin and Cunorix and (Maqui)coline are too great to allow for an identification. I would say that an argument based on the very uncertain ASC dates is hazardous at best and that if there is indeed a relationship between the pairs Ceawlin-Cynric and Coline-Cunorix, then the date of the memorial stone must be favored over that of the document.

There is also the problem of Cynric being the father of Ceawlin in the Anglo-Saxon tradition, while on the Wroxeter Stone it is (Maqui)coline who is the father of Cunorix. But such a confusion could easily have occurred simply by reading part of a genealogy list backwards.

While Ceawlin's father Cynric, the son of Cerdic of Wessex in most pedigrees, is capable of being derived quite well from Anglo-Saxon, the name could also be construed as an Anglicized form of the attested Celtic name Cunorix, Hound-king, the latter Welsh Cynyr.

Cerdic (= Ceredig) is not the only Celtic name in the early Wessex pedigree. Scholars have suggested that Ceawlin could be Brittonic.

Cunorix son of Maquicoline, based on an analysis of his name and the lettering employed on the inscription itself, is believed to have been Irish. It should not surprise us, then, to find Cunedda of Manau Gododdin, the reputed founder of Gwynedd, was himself actually Irish. There was an early St. Cuindid (d. c. 497 CE) son of Cathbad, who founded a monastery at Lusk, ancient Lusca. In the year entry 498 CE of the Ulster Annals, his name is spelled in the genitive as Chuinnedha. In Tigernach 496 CE, the name is Cuindedha.

The Irish sources also have the following additional information concerning St. Cuindid:

Mac Cuilind - Cunnid proprium nomen - m. Cathmoga m. Cathbath m Cattain m Fergossa m. Findchada m Feic m. Findchain m Imchada Ulaig m. Condlai m Taide m. Cein m Ailella Olum.

U496.2 Quies M. Cuilinn episcopi Luscan. (Repose of Mac Cuilinn, bishop of Lusca).

D.viii. idus Septembris. 993] Luscai la Macc Cuilinn

994] caín decheng ad-rannai, 995] féil Scéthe sund linni, 996] Coluimb Roiss gil Glandai.

trans: 'With Macc cuilinn of Luscae thou apportionest (?) a fair couple: the feast of Sciath here we have, (and that) of Columb of bright Ross Glandae'

The (later-dated) notes to this entry read: 'Lusk, i.e. in Fingall, i.e. a house that was built of weeds (lusrad) was there formerly, and hence the place is named Lusca ........Macc cuilinn, i.e. Luachan mac cuilinn, ut alii putant. Cuinnid was his name at first, Cathmog his father's name'.

Significantly, Lusk or Lusca is a very short distance from the huge promontory fort at Drumanagh, the Bruidhne Forgall Manach of the ancient Irish tales. Drumanagh is the hill of the Manapii and, as such, represents the Manapia in Manapii territory found on the map of Ptolemy. Manapii or Manapia could easily have been mistaken or substituted for for the Manau in Gododdin.

Aeternus, Cunedda's father, is none other than Aithirne of Dun and Ben Etair just south of Lusca. Paternus Pesrudd (‘Red-Cloak’), Cunedda's grandfather, is probably not derived from Mac Badairn of Es Ruad (‘Red Waterfall’), since Es Ruad is in northwest Ireland (Ballyshannon in Co. Donegal). I think Paternus, from the L. word for ‘father’, is Da Derga, the Red God; Da, god, being interpreted as W. tad (cf. L. tata, ‘father’). The Da Derga's hostel was just a little south of the Liffey. Cunedda's great-great-grandfather is said to be one Tegid (Tacitus), while his great-great-great grandfather is called Cein. These two chieftains are clearly Taig/Tadhg and his father Cian. Cian was the founder of the Irish tribe the Ciannachta, who ruled Mag Breg, a region situated between the Liffey and either Duleek or Drumiskin (depending on the authority consulted). The Lusca and Manapia of Chuinnedha are located in Mag Breg.

According to the genealogy edited in Corpus Genealogiarum Sanctorum Hiberniae, the name of Mac Cuilind's father was Cathmug. He belonged to the descendants of Tadc mac Cian, otherwise called the Cianachta. There was a concentration of the saints of this family in the Dublin/Louth/ Meath area, corresponding roughly to the teritory of the Cianachta Breg.

It is surely not a coincidence that according to the Irish Annals Chuinnedha's other name was Mac Cuilinn. Obviously, Mac Cuilinn and the Maqui-Coline of the Wroxeter Stone are the same name and hence the same person. Gwynedd was thus founded by Chuinnedha alias Mac Cuilinn of the Manapii in Ireland, not by a chieftain of Manau Gododdin in Britain.

The Irish origin of Cunedda should not be a surprise to us, as there is the well-documented case of the Welsh genealogy of the royal house of Dyfed, which was altered to hide the fact that Dyfed was founded by the Irish Deisi. We know this because we have the corresponding Irish genealogy from a saga which tells of the expulsion of the Deisi from Ireland and their settlement in Dyfed. As is true of Cunedda's pedigree, in the Welsh Dyfed pedigree we find Roman names substituted for Irish names. There were other Irish-founded kingdoms in Wales as well, e.g. Brycheiniog.

Monday, May 22, 2017

A new - but very tentative - identification of Medraut

Arthur Rackham's Illustration of Mordred and Arthur at Camlann

I long ago successfully etymologized the name Medraut as deriving from Latin/Roman Moderatus. Years ago Professor Oliver Padel agreed with me on this and others have since fallen into line. But I did not pursue the matter further - until now.

Here is the definition of moderatus from the online Perseus dictionary:

moderātus adj. with comp. and sup.

P. of moderor, within bounds, observing moderation, moderate : senes: Catone moderatior: consul moderatissimus: cupidine victoriae haud moderatus animus, S.—Plur m . as subst: cupidos moderatis anteferre.— Within bounds, moderate, modest, restrained : oratio: convivium: doctrina: ventus, O.: amor, O.: parum moderatum guttur, O.

The reader will note 'modest' is one meaning assigned to this word.

I will now turn to the pages of Gildas, where we are told Ambrosius Aurelianus was a 'viro modesto', a MODEST man.

For the sake of comparison, here is the same dictionary's definition for modestus:

modestus adj. with comp. and sup.

modus, keeping due measure, moderate, modest, gentle, forbearing, temperate, sober, discreet : sermo, S.: adulescentis modestissimi pudor: plebs modestissima: epistula modestior: voltus, T.: verba, O.: mulier, modest , T.: modestissimi mores: voltus modesto sanguine fervens, Iu.—As subst: modestus Occupat obscuri speciem, the reserved man passes for gloomy , H.

Both Latin modestus and moderatus are found the Indo-European root med-,'to measure, to allot, to mete out':

3. Suffixed form *med-es-.

a. modest; immodest from Latin modestus, "keeping to the appropriate measure" moderate;

b. moderate; immoderate from Latin moderārī, "to keep within measure" to moderate, control. Both a and b from Latin *modes-, replacing *medes- by influence of modus

Thus the words modestus and moderatus are consonant in meaning.

Ambrosius (the 'divine/immortal one'), before he was wrongly identified with Lleu/Mabon of Gwynedd (and later still with Myrddin of the North), was said to have fought a battle at Wallop in Hampshire. This is not too far north of the battle sites ascribed to Arthur/Cerdic/Ceredig son of Cunedda. In addition, the Camlann sites in NW Wales are in Gwynedd.

While it may seem a stretch to identify Medraut/Moderatus with the viro modesto who was Ambrosius, it is possible that by the time Arthur had come to the forefront as the chief hero of the Welsh in the work of the 9th century Nennius, someone had found it necessary to "disguise" the fact that the latter had died fighting the former champion of the Britons, the 'last of the Romans.' Alternatively, the 'viro modesto' of Gildas may have been a simple substitution for Moderatus, this last having been mistaken for an adjective rather than a proper name.

We must also remember that the earliest reference to the deaths of Arthur and Medraut - that of the Welsh Annals - does not tell us whether these two chieftains were fighting together against a common foe or against each other. Chronological problems also occur, especially if we accept my earlier identification of Ambrosius Aurelianus with the 4th century Gaulish governor of that name. Most Arthurian scholars prefer to see in A.A. someone of the 5th century who had been named after the governor or who was somehow related to him. I've shown in the past that St. Ambrose, son of the governor, also became confused in some respects with the military leader A.A.

We can only say this much if A.A. really was 'Medraut': the Camboglanna Roman fort at the west end of Hadrian's Wall is out of the running as Arthur's Camlann. As Arthur was Ceredig of Ceredigion, and Ceredigion bordered on the Camlanns in Gwynedd, and as A.A. became in legend the Lord of Gywnedd (= Lleu/Mabon), the only good candidates for Camlann are those in NW Wales.

A last possibility has only recently occurred to me: that the ruler at Dinas Emrys was originally called Moderatus, and that this name became confused with that of the modest man A.A. In Welsh tradition (whether due to Geoffrey of Monmouth or not!), Medraut was the son of Lleu - the very god who was anciently claimed as Lord of Gwynedd. So we may have a chieftain named Medraut whose main citadel was Dinas Emrys, and who claimed descent from the god Lleu. This chieftain fought at the Camlann which lay between his kingdom and that of Ceredigion and at that battle he and Arthur/Ceredig both fell.

I realize that I've now made the identity of A.A. even murkier. But I may have at least shed a little more light on who Medraut really was.

In conclusion, I acknowledge the fact that this idea is not very convincing. Suffice it to say it is an interesting coincidence.

Saturday, May 20, 2017

The Long Graves at Gwanas (site of Arthur's grave in Welsh tradition?)

In a previous blog entry, I discussed the possibility that - at least as far as the Welsh were concerned - Arthur may have been buried at Gwanas in Gwynedd (http://mistshadows.blogspot.com/2016/12/anoeth-bin-u-bedd-arthur-and-caer-oeth.html).

I've subsequently investigated the area in more detail, and have discovered an interesting candidate for the so-called 'beddau hir' or long graves of Gwanas.

The best account of this candidate is found on the COFLEIN site (http://www.coflein.gov.uk/en/site/54526/details/lletty-canol-possible-roman-signal-station-above-brithdir), which I will here quote in full:

I've subsequently investigated the area in more detail, and have discovered an interesting candidate for the so-called 'beddau hir' or long graves of Gwanas.

Aerial Photo of Enclosure Near Lletty Canol

Lletty Canol Enclosure, Shown in Proximity to Both the Brithdir Roman Fort and Gwanas Moor

The best account of this candidate is found on the COFLEIN site (http://www.coflein.gov.uk/en/site/54526/details/lletty-canol-possible-roman-signal-station-above-brithdir), which I will here quote in full:

"A small square earthwork set upon a ridge summit has been identified as a possible Roman military tower. It is set on the crest of a south-facing ridge, commanding extensive views across the upland basin below Pen-y-Brynnfforchog and the course of the Roman road between Caer Gai and Brithdir.

A range of alternative interpretations can be advanced, notably that this is a Roman or early Medieval square ditched barrow, such as are found at Druid beyond Bala (NPRN 404711), and Croes Faen near Tywyn (NPRN 310263). As such it would, with Tomen-y-Mur (NPRN 89420), be a rare surviving earthwork example, most sites being known only from cropmarks. This monument might be compared to the small practice work at Llyn Hiraethllyn (NPRN 89703), otherwise the smallest example of its type known in Wales.

It is a square platform about 5.0m across with a shallow ditch up to 2.8m across on the south-east, 1.1m wide on the north-east and south-west and not discernable on the north-west. The platform has low banks on the north-east and south-west sides. As a Roman work the earthwork has been associated with a road or track passing below the ridge to the south-east (NPRN 91903), suggested as part of the Roman road between Caer Gai and Brithdir (Rigg & Toller 1983, 165; Britannia XXVIII (1997), 399), although this has been disputed as it is a modern feature (Browne 1986) and is depicted on the 1st edition OS 1" map of 1837 (sheet 59 north-east). A tower on this site would command extensive views of the tributary valley to the south-east, but not of the main Wnion valley on the north-west and the Brithdir military settlement (NPRN 95480) may be out of sight. The earthwork is intervisible with the 'Rhyd Sarn' works 11.5km to the north-east towards Bala Lake (NPRN 303162-3)."

The 'low banks' of this monument (if that is what it really is!) nicely answer for the 'long graves' of Gwanas. Caer Oeth and Anoeth would be the Brithdir fort itself. Whether Arthur was thought to have been buried at the fort or at the adjacent funeral monument is not a question we can answer.

There are no other candidates for the beddau hir. Of course, time and the combined ravages of Man and Nature may long since have destroyed any other such monuments in the region.

Friday, May 19, 2017

Cerdic/Ceredig/Arthur and the 'Ictian Sea'

Celtic Tribes of Britain

In previous blog entries I have outlined my fairly detailed case for the famous Arthur being Cerdic of Wessex, himself a mercenary chieftain who can be identified with Ceredig son of Cunedda of western Wales. This Cerdic/Ceredig was Irish or perhaps Hiberno-British.

Here I wish to briefly discuss the Irish literary "evidence" for the presence of Irish raiders and even Irish kings in that part of Britain where Cerdic of Wessex was most active.

In the SANAS CORMAIC (c. 900 A.D.), we are told that the Irish during the time of the half-legendary 4th century king Crimthann Mar mac Fidaig, held "Ireland and Alba [Britain]... down to the Ictian Sea [English Channel, named for the Isle of Wight, ancient Vectis]..." Cerdic of Wessex, of course, is billed as the conqueror of the Isle of Wight, while his other recorded victorious battles were in southern Hampshire opposite Wight. If, according to Cormac's Glossary, the Irish held this area during the 4th century, might it not also be true that they came to control it in alliance with the Saxons in the 5th-6th centuries under Cerdic/Ceredig?

The famous Njal of the Nine Hostages (probably 5th century) is also brought into connection with the English Channel - and in a most peculiar, even perhaps, suspicious way. The 10th century poet Cinaed ua hArtacain tells us that Njal engaged in seven raids of Britain (Alba being in other accounts confused with the European Alps!). In the last he was slain by Eochu or Eochaid the Leinsterman "above the surf of the Ictian Sea." My question when I read this account focused on the name of Najl's killer. For both Eochu and Eochaid contain the ancient Irish word for 'horse'. The following is from the thesis on the names prepared by Professor Jurgen Uhlich, Professor of Irish and Celtic Languages, Trinity College, Dublin:

EOCHAID [and many variants]:

z.B. 'dem Pferd(egott) dienend/genehm' = e.g. ‘serving the horse(-god)’ or ‘acceptable to the horse(-god)'

EOCHAID [and many variants]:

z.B. 'dem Pferd(egott) dienend/genehm' = e.g. ‘serving the horse(-god)’ or ‘acceptable to the horse(-god)'

EOCHU:

z.B. [Bv.] ‚pferdeäugig‘ oder „‘Qui a la voix du Cheval (prophétique)’ = qui parle selon les indications fournies par le Cheval prophétique“ = e.g. ‘horse-eyed’ or ‘having a Horse’s (prophetic) voice’ = ‘he who speaks according to the insights provided by the Horse-prophet'

As we all know, Kent, named for the ancient British tribe of the Cantiaci, was a kingdom on the English Channel. The supposed founders of Kent for Hengest ('Stallion') and Horse ('Horse'). Could it possibly be that Eochu/Eochaid in the story of the slaying of Njal on the English Channel is an Irish substitute for one of these English horse names? That Njal was, in reality, slain by Hengest and/or Horsa? The idea is not as absurd as it may seem, for Eochu/Eochaid is said to have killed Njal "in concert with the violent grasping Saxons."

Coin of Eppilus

Hengest and Horsa, in turn, have before been associated with an ancient British king named Eppilus. There were one or two kings of this name, one of the Atrebates and the other of the Cantiaci. The name contains the word for 'horse', i.e. epo- (epos), as is made clear by the authoritative CELTIC PERSONAL NAMES OF ROMAN BRITAIN website (http://www.asnc.cam.ac.uk/personalnames/details.php?name=245).

Eppilus minted coins with horses on them. His brother was one Tincomarus, 'Great Peace' or the like. However, one cannot help but wonder if the -marus element in this last name did not remind the Saxons of their own early word mearh; g. meares; m. A horse, steed? We now have this word as mare, a female horse, but that was not its original meaning. Words from the same Indo-European root are found in the Celtic languages, e.g. Welsh march. However, Old English also had eoh for 'horse, steed', and this word is cognate with the Irish ech, itself the basis for names such as Eochu and Eochaid.

If Eppilus and Tincomarus were interpreted as divinely ruling horse-brothers, could it be that the Saxon brothers Hengist and Horsa are merely later reflections of these earlier Celtic kings, adopted by the Germanic federates or invaders? Or that two Saxons who were credited with conquering Kent were actually named for their famous British predecessors?

Scholars have tried to form a connection between Hengist and Horsa and the Alcis, twin gods of the Naharnavali tribe in Silesia. This is a stretch, however. Of the several etymologies proposed for the word Alcis, one does relate it to "elks". But elks, needless to say, are not horses. Rudolf Simek (in his DICTIONARY OF NORTHERN MYTHOLOGY), points out the presence of a horse-shaped variant of the Germanic twin god motif in Migration Era illustrations.

Scholars have tried to form a connection between Hengist and Horsa and the Alcis, twin gods of the Naharnavali tribe in Silesia. This is a stretch, however. Of the several etymologies proposed for the word Alcis, one does relate it to "elks". But elks, needless to say, are not horses. Rudolf Simek (in his DICTIONARY OF NORTHERN MYTHOLOGY), points out the presence of a horse-shaped variant of the Germanic twin god motif in Migration Era illustrations.

Saturday, May 13, 2017

COMING SOON: Cerdic/Ceredig/Arthur and the 'Ictian Sea'

Isle of Wight and The Solent

And a side-note on Njal's death at the hands of Eochaid in the surf of the Ictian Sea...

Saturday, April 22, 2017

Cunedda, Carlisle, Durham - and Camboglanna?

Map Showing Camboglanna and Aballava in Relation to Carlisle/Luguvalium

In my book THE ARTHUR OF HISTORY, one of the proofs I supplied for a historical Arthur based on the western end of Hadrian's Wall was the presence of some Roman fort names that seemed to match up very well with famous place-names found in the Arthurian tradition. Chief among these was Camboglanna (= Camlann?) and Aballava (or Avalana, = Avalon?). However, my more recent research, which opts instead for an Arthur originating from the kingdom of Ceredigion, made it seem much more likely that Camlann is to be identified with one of the sites of that name in NW Wales. It seemed possible, therefore, that 'Avalon' was conjured up as the burial place of Arthur because one of the Welsh Camlanns was confused with the Camboglanna fort on the Wall.

An ancient Welsh poem called MARWNAD CUNEDDA, or the "Death-Song of Cunedda", may allow for us to have our cake and eat it, too, in a sense. In this poem (http://www.celtic-twilight.

Carlisle, the earlier Roman fort of Luguvalium, is directly between the Camboglanna and Aballava forts. If Cunedda really were fighting here, and his sons (or teulu) were with him at the time, then it is certainly conceivable that Ceredig/Arthur fought and died at Camboglanna. This would appear to be in contradistinction to Ceredig (or Cerdic) fighting in the extreme south of England.

There are two possibilities, as I see it. First, as a mercenary chieftain (or federate in the old Roman style), Ceredig/Arthur was literally fighting all over the place. There is nothing wrong with this notion and it cannot, on the face of things, be objected to. We do have to remember, though, that Cunedda himself was falsely associated with the Far North when he was converted from an Irishman into a Briton with bogus Roman ancestry. The same death-song, for example, has him being militarily active in Bernicia, which at its maximum extent eventually bordered right on Manau Gododdin, the region substituted for that around Drumanagh in Ireland. Thus it could well be that these northern locations with which Cunedda became associated represent fictional elements in his exploits. In other words, as he came to be seen as a great British chieftain of the North, who at some point in his career came down and conquered or settled in NW Wales, it was deemed necessary to provide a "history" for him that preceded his actions in Gwynedd.

So, did Arthur die at Camboglanna on the Wall or at one of the Camlanns in NW Wales? Given that the Welsh Camlanns are just a little north of Ceredigion, it seems logical to at least prefer them over the Roman fort on the Wall. Welsh tradition insisted from early on the the conflict between Arthur and Medraut was an internecine one. We might imagine, then, a border dispute between Ceredigion and Meirionydd, or merely aggressive movement of the former into the latter. Yet we must temper this view with my previous argument for Medraut (Modred, etc.) as a form of the Latin name Moderatus, which was borne by a prefect in the Cumbria region during the Roman period.

An ancient Welsh poem called MARWNAD CUNEDDA, or the "Death-Song of Cunedda", may allow for us to have our cake and eat it, too, in a sense. In this poem (http://www.celtic-twilight.

Carlisle, the earlier Roman fort of Luguvalium, is directly between the Camboglanna and Aballava forts. If Cunedda really were fighting here, and his sons (or teulu) were with him at the time, then it is certainly conceivable that Ceredig/Arthur fought and died at Camboglanna. This would appear to be in contradistinction to Ceredig (or Cerdic) fighting in the extreme south of England.

There are two possibilities, as I see it. First, as a mercenary chieftain (or federate in the old Roman style), Ceredig/Arthur was literally fighting all over the place. There is nothing wrong with this notion and it cannot, on the face of things, be objected to. We do have to remember, though, that Cunedda himself was falsely associated with the Far North when he was converted from an Irishman into a Briton with bogus Roman ancestry. The same death-song, for example, has him being militarily active in Bernicia, which at its maximum extent eventually bordered right on Manau Gododdin, the region substituted for that around Drumanagh in Ireland. Thus it could well be that these northern locations with which Cunedda became associated represent fictional elements in his exploits. In other words, as he came to be seen as a great British chieftain of the North, who at some point in his career came down and conquered or settled in NW Wales, it was deemed necessary to provide a "history" for him that preceded his actions in Gwynedd.

So, did Arthur die at Camboglanna on the Wall or at one of the Camlanns in NW Wales? Given that the Welsh Camlanns are just a little north of Ceredigion, it seems logical to at least prefer them over the Roman fort on the Wall. Welsh tradition insisted from early on the the conflict between Arthur and Medraut was an internecine one. We might imagine, then, a border dispute between Ceredigion and Meirionydd, or merely aggressive movement of the former into the latter. Yet we must temper this view with my previous argument for Medraut (Modred, etc.) as a form of the Latin name Moderatus, which was borne by a prefect in the Cumbria region during the Roman period.

Monday, April 17, 2017

Sunday, April 9, 2017

New artwork for my next Arthur book

I will be using this image of the Bootle, Lancashire jet bear for the cover of my new book THE BEAR KING: ARTHUR AND THE IRISH IN WESTERN AND SOUTHERN BRITAIN:

Thursday, March 9, 2017

UPDATE on Aerfen, goddess of the River Dee

In an earlier post (http://mistshadows.blogspot.com/2017/01/st-aaron-goddess-aeruen-and-city-of.html), I suggested that St. Aaron of the City of the Legion was a Christian substitute for the goddess Aerfen/Aeruen of the River Dee.

I've since had confirmation back from the National Library of Wales regarding false claims made concerning this goddess by neopagan writers:

Thus while she is mentioned in early Welsh sources, it is patently untrue that a shrine to her was known of, and that sacrifices were regularly offered to her. These are stories made up by modern authors which have infiltrated some other more respectable sources and are, therefore, all too often interpreted as facts.

I've since had confirmation back from the National Library of Wales regarding false claims made concerning this goddess by neopagan writers:

Thus while she is mentioned in early Welsh sources, it is patently untrue that a shrine to her was known of, and that sacrifices were regularly offered to her. These are stories made up by modern authors which have infiltrated some other more respectable sources and are, therefore, all too often interpreted as facts.

Saturday, March 4, 2017

The Family of the Real Arthur (Ceredig son of Cunedda)

GWAWL, MOTHER OF CEREDIG SON OF CUNEDDA

According to the early Welsh genealogies, the mother of Ceredig son of Cunedda (in a later source called the mother of Cunedda) was named Gwawl. She was supposedly a daughter of Coel Hen of the North, a common progenitor of early princely lines. Although some have disagreed, Coel himself is likely a eponym created for the Kyle region of South Ayrshire in southern Scotland.

Gwawl is though to mean (GPC) 'light, brightness, radiance, splendour; bright'. This would be a very pretty name for a woman, and an especially apt one for a queen. Unfortunately, there is a another word in Welsh spelled exactly the same which leads us to a different conclusion regarding Ceredig's mother. Here is a page from P.C. Bartram's A CLASSICAL WELSH DICTIONARY:

Gwawl is 'wall' in Welsh. For Gwawl son of Clud (Clud being an eponym for the Clyde), it designates the Antonine Wall. As Cunedda was wrongly said to have come from Manau Gododdin, a region which stretched to both sides of the same Roman defensive barrier, it seems pretty obvious to me that Gwawl was chosen as the name of Ceredig's mother for exactly this reason, i.e he and his father were said to have originated or were "born" from the eastern end of the Antonine Wall.

MELERI, WIFE OF CEREDIG SON OF CUNEDDA

According to Dr. Simon Rodway of the University of Wales, Meleri is a hypocoristic form of Eleri. 'My', which means the same as our word my, is affixed to the front of the name as a term of endearment, viz. 'My Eleri.' Eleri itself is a Welsh form of the Latin name Hilarius, from hilaris, 'cheerful, merry.'

Meleri is one of the many daughters of Brychan, the eponymous IRISH founder of the kingdom of Brycheiniog. which lay to the southeast of Ceredigion.

CHILDREN OF CEREDIG AND MELERI

Of the progeny of Ceredig, we can do nothing better than cite Bartram once again:

To me the most interesting person here is the daughter Gwawr, mother of Gwynllyw. In a previous post (http://mistshadows.blogspot.com/2016/09/a-curious-coincidence-of-meaning.html), I discussed the Coedkernyw in Gwynllwg, a petty kingdom named for Gwynllyw, as well as the Celliwig located in the same vicinity. Arthur in Welsh tradition is always strongly associated with a Kernyw and also with a Celliwig. Gwynllwg was near Caerleon, the site of the City of the Legion where Arthur fought a battle according to the Historia Brittonum, and not far from the trajectus or Tribruit across the Severn where he fought another.

The son Carannog also plays into the story of Arthur, albeit more directly. He is the saint of that name from the Vita:

According to the early Welsh genealogies, the mother of Ceredig son of Cunedda (in a later source called the mother of Cunedda) was named Gwawl. She was supposedly a daughter of Coel Hen of the North, a common progenitor of early princely lines. Although some have disagreed, Coel himself is likely a eponym created for the Kyle region of South Ayrshire in southern Scotland.

Gwawl is though to mean (GPC) 'light, brightness, radiance, splendour; bright'. This would be a very pretty name for a woman, and an especially apt one for a queen. Unfortunately, there is a another word in Welsh spelled exactly the same which leads us to a different conclusion regarding Ceredig's mother. Here is a page from P.C. Bartram's A CLASSICAL WELSH DICTIONARY:

Gwawl is 'wall' in Welsh. For Gwawl son of Clud (Clud being an eponym for the Clyde), it designates the Antonine Wall. As Cunedda was wrongly said to have come from Manau Gododdin, a region which stretched to both sides of the same Roman defensive barrier, it seems pretty obvious to me that Gwawl was chosen as the name of Ceredig's mother for exactly this reason, i.e he and his father were said to have originated or were "born" from the eastern end of the Antonine Wall.

MELERI, WIFE OF CEREDIG SON OF CUNEDDA

According to Dr. Simon Rodway of the University of Wales, Meleri is a hypocoristic form of Eleri. 'My', which means the same as our word my, is affixed to the front of the name as a term of endearment, viz. 'My Eleri.' Eleri itself is a Welsh form of the Latin name Hilarius, from hilaris, 'cheerful, merry.'

Meleri is one of the many daughters of Brychan, the eponymous IRISH founder of the kingdom of Brycheiniog. which lay to the southeast of Ceredigion.

CHILDREN OF CEREDIG AND MELERI

Of the progeny of Ceredig, we can do nothing better than cite Bartram once again:

To me the most interesting person here is the daughter Gwawr, mother of Gwynllyw. In a previous post (http://mistshadows.blogspot.com/2016/09/a-curious-coincidence-of-meaning.html), I discussed the Coedkernyw in Gwynllwg, a petty kingdom named for Gwynllyw, as well as the Celliwig located in the same vicinity. Arthur in Welsh tradition is always strongly associated with a Kernyw and also with a Celliwig. Gwynllwg was near Caerleon, the site of the City of the Legion where Arthur fought a battle according to the Historia Brittonum, and not far from the trajectus or Tribruit across the Severn where he fought another.

The son Carannog also plays into the story of Arthur, albeit more directly. He is the saint of that name from the Vita:

Wednesday, March 1, 2017

Monday, February 27, 2017

Scholars no. 3, 4 and 5 weigh in on my identification of Iusay son of Ceredig with the Gewissae/Gewissei

From Professor Doctor P.C.H. Schrijver, Department of Languages, Literature and Communication, Celtic, Institute for Cultural Inquiry, University of Utrecht -

"Linguistically, the first thing that comes to mind regarding the initial alternation Usai /Iusay is the pair OW iud, MW udd 'lord' < *iüdd. So OW word-initial j- disappears in front of ü (= MW u). As to your assumption that Iusay may be connected to Gewissae if there is a rule that states that medial -i- is lost, I can tell you that there is indeed such a rule: *wi > ü in non-final syllables (as in *wikanti: > MW ugeint, see my Studies in British Celtic Historical Phonology 159-60). This generates the ü that we need in order to later get rid of the initial j. The only remaining problem is connecting OE Ge- /je/ with OW j-. Barring that, I would say, yes, what you suggest is possible. That still leaves the origin and etymology of the name in the dark (the reconstruction leads to something like *iwissai- or *g/jewissai-), but first things first."

From Professor Doctor Stefan Zimmer, Department of Celtic, University of Bonn -

"Spontaneaously, your idea of interpreting "Iusay" as a W form of OE Gewisse seems quite attractive. One must, of course, check meticulously the palaeographic details. As I am, alas, not a palaeograher myself, I cannot say more. I see no "LINGUISTIC" problems."

From Professor Patrick Sims-Williams, Department of Welsh and Celtic Studies, The University of Wales, Aberystwyth -

"I suppose Ius- is the older form and became Us- like Iustic in Culhwch which becomes Usic. Forms of Gewissae are noted by Williams/Bromwich Armes Prydein pp. xv-xvi. One Welsh form is Iwys, which rhymes as I-wys, and as the diphthong wy can become w, you could get I-ws- which could be written Ius- in Old Welsh and then add -ae from Latin which almost gets you to Iusay."

"Linguistically, the first thing that comes to mind regarding the initial alternation Usai /Iusay is the pair OW iud, MW udd 'lord' < *iüdd. So OW word-initial j- disappears in front of ü (= MW u). As to your assumption that Iusay may be connected to Gewissae if there is a rule that states that medial -i- is lost, I can tell you that there is indeed such a rule: *wi > ü in non-final syllables (as in *wikanti: > MW ugeint, see my Studies in British Celtic Historical Phonology 159-60). This generates the ü that we need in order to later get rid of the initial j. The only remaining problem is connecting OE Ge- /je/ with OW j-. Barring that, I would say, yes, what you suggest is possible. That still leaves the origin and etymology of the name in the dark (the reconstruction leads to something like *iwissai- or *g/jewissai-), but first things first."

From Professor Doctor Stefan Zimmer, Department of Celtic, University of Bonn -

"Spontaneaously, your idea of interpreting "Iusay" as a W form of OE Gewisse seems quite attractive. One must, of course, check meticulously the palaeographic details. As I am, alas, not a palaeograher myself, I cannot say more. I see no "LINGUISTIC" problems."

From Professor Patrick Sims-Williams, Department of Welsh and Celtic Studies, The University of Wales, Aberystwyth -

"I suppose Ius- is the older form and became Us- like Iustic in Culhwch which becomes Usic. Forms of Gewissae are noted by Williams/Bromwich Armes Prydein pp. xv-xvi. One Welsh form is Iwys, which rhymes as I-wys, and as the diphthong wy can become w, you could get I-ws- which could be written Ius- in Old Welsh and then add -ae from Latin which almost gets you to Iusay."

Sunday, February 26, 2017

FUTURE BOOK ANNOUNCEMENT - "The Bear King: Arthur and the Irish in Wales and Southern England"

The Meigle "Caledonian Bear"

It may take me awhile to get to it (and to finish it!), but I plan a new book on "King" Arthur. This one will bring together my various posts on a Hiberno-British Arthur whom I've identified with Ceredig son of Cunedda/Cerdic of Wessex.

My old book, THE ARTHUR OF HISTORY, will remain available here and at Amazon (paper and ebook formats). It might seem wise to remove this one from sale or from a free blog site, but as it still contains what I feel to be much valuable information, I will suffer its continued existence - even though the new book offers an entirely new and different historical Arthur candidate. My decision regarding THE ARTHUR OF HISTORY is also partly a matter of intellectual honesty. Over the years I've never been afraid to change my mind when evidence or compelling argument forced me to do so. I do not plan to change that approach now. If some readers consider me "wishy-washy" as a result, I can live with that. There is nothing worse than stubbornly sticking with an invalid theory for no other reason than the desire to protect one's ego or scholarly reputation.

Once again, the production of this next book will be anything but quick. But if fortune favors me, I will eventually get it done.

Friday, February 24, 2017

Brief update on the hill-fort at Llandewi Aberarth

I've finally heard back from Lynne Moore, Enquiries and Library Officer with the Royal Commission on the Ancient and Historical Monuments of Wales regarding the hill-fort at Llandewi Aberarth, which I've tentatively suggested might have been the main fortress of Ceredig son of Cunedda:

"As suggested by Dyfed Archaeological Trust, the hilltop enclosure (a possible Iron Age hillfort) was noted by ourselves (RCAHMW) during a flight to take aerial photographs of the area. Please note that the RAF APs, and the earlier RCAHMW APs, exist only in hard-copy form."

"As suggested by Dyfed Archaeological Trust, the hilltop enclosure (a possible Iron Age hillfort) was noted by ourselves (RCAHMW) during a flight to take aerial photographs of the area. Please note that the RAF APs, and the earlier RCAHMW APs, exist only in hard-copy form."

Saturday, February 18, 2017

More and more positive feedback coming concerning my identification of Iusay son of Ceredig with the Gewissae/Gewissei

In my blog article at http://mistshadows.blogspot.com/2017/02/gewis-gewissaegewissei-and-iusay-son-of.html, I've started adding supportive comments by top Celtic linguists to my case that Iusay son of Ceredig = the Gewissae/Gewissei.

Most of the scholars providing positive feedback are not privy to my various arguments seeking to prove that Cunedda and his sons were of Irish (or Hiberno-British) origin. They have been queried only on the linguistic aspect of the problem involving an etymology for Iusay.

I will continue to add more material from the scholars as I receive it.

Most of the scholars providing positive feedback are not privy to my various arguments seeking to prove that Cunedda and his sons were of Irish (or Hiberno-British) origin. They have been queried only on the linguistic aspect of the problem involving an etymology for Iusay.

I will continue to add more material from the scholars as I receive it.

Wednesday, February 15, 2017

GEWIS, THE GEWISSAE/GEWISSEI AND IUSAY SON OF CEREDIG SON OF CUNEDDA

Cerdic of Wessex in the film 'King Arthur'

Many years ago I floated the idea that Iusay, son of Ceredig son of Cunedda, may be a form of the family/tribal designation Gewissae or Gewissei. While a proposed relationship between these names was not well-received, I would like to briefly revisit the possibility here.

The forms Gewissei and Gewissae are attested (see Richard Coates "On some controversy surrounding Gewissae / Gewissei, Cerdic and Ceawlin").

The later Welsh forms Iwys or Iwis for the Gewissae would appear to derive from the Anglo-Saxon form of this word. Simon Rodway has confirmed for me that "Iwys is the Welsh form of Gewissae (Armes Prydein, ed. Ifor Williams, English version by Rachel Bromwich (Cardiff, 1972), pp. 49-50)."

Alfred is king of the "giuoys", i.e. Gewissae, in Welsh Annal entry AD 900. Asser says in his LIFE OF ALFRED: "Cerdic, who was the son of Elesa, who was the son of Geuuis, from whom the Britons name all that nation Geguuis [Gewissae]."

Iusay (variant Usai) has not been successfully etymologized by the Celtic linguists. Recently, I sent queries to several, all of whom were forced to admit that they could not come up with an acceptable derivation. I myself have tried everything I could think of, including Classical and Biblical names. This attempt ended in failure. Although there are some forms of Biblical names as recorded in Irish texts (like Usai), the initial /I-/ of Iusay prohibits us from identifying such with the Welsh name. A Ius- might suggest a Roman name like Justus, but then we cannot account for the ending of Iusay/Usai.

Of course, it is possible Iusay and Usai are corrupt or that they represent some Welsh mangling of an Irish name. Neither I nor the language experts have been able to find such an Irish analog. This is not to say it does not exist, merely that we have been unable to find it.

All of which brings me back to this:

I have shown in previous research that the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle's Cerdic is Ceredig son of Cunedda, that the same source's Cynric is Cunorix son of Cunedda (as Maquicoline) and that Ceawlin, supposed son of Cynric is, in fact, Cunedda (Maquicoline). Sisam and Dumville have aptly proven that Elesa (= the metathesis Esla) is a borrowing from the Bernician pedigree. Omitting Elesa, then, permits us to see Gewis, eponym of the Gewissei/Gewissae, as the immediate ancestor of Cerdic/Ceredig. As the genealogy in the ASC in the main runs backwards, it may be that Gewis/Gewissae/Gewissei is properly the son of Ceredig.

If so, we might be able to account for Iusay after all. It is well known that the /G-/ of Gewis or Gewissei/Gewissae came to be pronounced as a /Y-/. This is what accounts for the Welsh forms beginning in /I-/. /W/ and /U/ regularly substitute for each other, especially when going from Welsh to Latin (cf. gwyn and guin). If the terminal diphthong in Iusay/Usai represents the /-ei/-ae/ of Gewissae/Gewissei, then we need only allow for a lost medial small vowel /-i-/. Iusay would then be a Welsh form of not Gewis, but of the group designation Gewissae/Gewissei.

I feel this is a rather elegant solution to the problem posed by the name Iusay.

NEW FEEDBACK FROM TOP CELTIC SCHOLARS ON IUSAY = GEWISSAE/GEWISSEI (I WILL CONTINUE TO ADD TO THIS SECTION AS I RECEIVE MORE COMMUNICATIONS FROM SENT QUERIES):

From Professor Oliver Padel Honorary Research Fellow in the Department of Anglo-Saxon, Norse and Celtic, University of Cambridge -

"In fact I think your suggestion is not only ingenious but also quite convincing. The only difficult bit, I suppose, is how a tribal name came to be thought of as an individual personal name.

The I- for OE Ge- is fine, of course; as for its loss (Iu- becoming U-), one might think of the wider Welsh loss of I- in words beginning Iu-, such that original iudd (`lord') became udd (I'm using Modern Welsh spellings for clarity), and personal names containing that word as an element did likewise. (You will find details in Jackson's Language & History in Early Britain -- sorry I haven't got it to hand)."

early Welsh genealogies (I completed a PhD on the subject last year). I'm

happy to help if I'm able.

I think you're right that no etymology has been proposed for 'Iusay/Usai'

before. What you propose is certainly an intriguing suggestion, but I think

that you may encounter a couple of difficulties with it. Firstly, as you

point out below, there appears to be one too few minims in Iusay for it to

equate to Gewisse/Iwys. Welsh forms of Gewisse, of which the best known is

in Armes Prydein Vawr, always appear as Iwis or Iwys (compare the examples

listed in GPC online). There are also earlier forms that point to the same

thing: 'Giuoys' in Annales Cambriae A, s.a. 899, and Asser's 'Geguuis'. But

as you suggest, this is not an insurmountable problem - though the loss

would be more readily explained on a palaeographical rather than

phonological level. The greater problem is the '-ay/-ai' ending. Comparable

endings appear in the English forms because they survive in Latinate

contexts - chiefly Bede's nominative plural form 'Geuissae' and a genitive

plural 'Gewisorum' (implying a Latin nom. pl. 'Gewisi') in some Anglo-Saxon

charters (as mentioned in the Keynes-Lapidge Asser book, p. 229). I don't

think that that kind of ending would be expected in an OE context, and it

certainly wouldn't in Welsh - GPC takes Iwys as a plural or collective noun

whose ending has been influenced by the plural noun ending -wys (< Lat.

-enses) found in words like 'Gwennwys'. So in other words, for your proposed

derivation to work, Iusay would have to be a version of a Latinate form such

as Bede's 'Geuissae'. The question of how that got into the Ceredigion

genealogy in the form 'Iusay' would then be all the more complex, and

wouldn't be solely a matter of linguistics! That's not to say that you're

necessarily incorrect, of course, but it would require a more elaborate, and

therefore more speculative, theory of derivation.

There is one further thing you might consider though, if you wanted to

pursue this further: the genealogy of St Cadog. This survives in two

versions, one appended to the Life of St Cadog, the other in the Jesus

College 20 genealogies. The former calls Cadog's great-grandfather 'Solor',

the latter 'Filur'. Both of these names were probably copied ultimately from

'Silur' or the like. Given where St Cadog's cult centre is (Llancarfan),

this can't be anything other than a representation of the pre-Roman tribe

'Silures', who were resident in that area. But the form 'Silur' is not the

result of regular linguistic development from the 1st century AD; it is a

form taken at a later stage from a Latin text, with the '-res' ending lopped

off. This might help you envisage the kind of process that might have led to

a Latinate form such as Bede's 'Geuissae' being included in the Ceredigion

pedigree, but one has to make rather more leaps to get there!"

From Professor Doctor P.C.H. Schrijver, Department of Languages, Literature and Communication - Celtic, Institute for Cultural Inquiry, University of Utrecht -

"Linguistically, the first thing that comes to mind regarding the initial alternation Usai /Iusay is the pair OW iud, MW udd 'lord' < *iüdd. So OW word-initial j- disappears in front of ü (= MW u). As to your assumption that Iusay may be connected to Gewissae if there is a rule that states that medial -i- is lost, I can tell you that there is indeed such a rule: *wi > ü in non-final syllables (as in *wikanti: > MW ugeint, see my Studies in British Celtic Historical Phonology 159-60). This generates the ü that we need in order to later get rid of the initial j. The only remaining problem is connecting OE Ge- /je/ with OW j-. Barring that, I would say, yes, what you suggest is possible. That still leaves the origin and etymology of the name in the dark (the reconstruction leads to something like *iwissai- or *g/jewissai-), but first things first."

From Professor Doctor Stefan Zimmer, Department of Celtic, University of Bonn -

"Spontaneaously, your idea of interpreting "Iusay" as a W form of OE Gewisse seems quite attractive. One must, of course, check meticulously the palaeographic details. As I am, alas, not a palaeograher myself, I cannot say more. I see no "LINGUISTIC" problems."

From Professor Patrick Sims-Williams, Department of Welsh and Celtic Studies, The University of Wales, Aberystwyth -

"I suppose Ius- is the older form and became Us- like Iustic in Culhwch which becomes Usic. Forms of Gewissae are noted by Williams/Bromwich Armes Prydein pp. xv-xvi. One Welsh form is Iwys, which rhymes as I-wys, and as the diphthong wy can become w, you could get I-ws- which could be written Ius- in Old Welsh and then add -ae from Latin which almost gets you to Iusay."

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)